- About Us

- Events & Training

- Professional Development

- Sponsorship

- Get Involved

- Resources

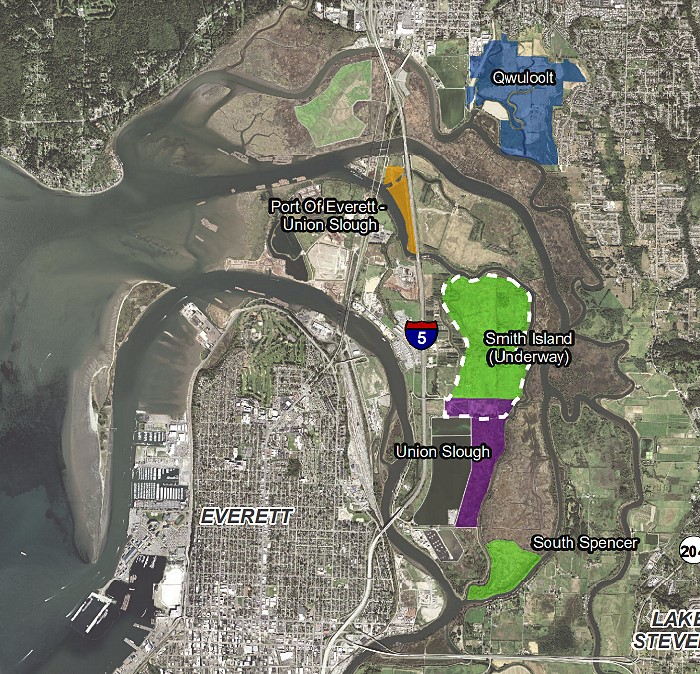

The Snohomish River WatershedJohn Owen with contributions by Amy Brockhaus and Erika HarrisThe first image of this “blog” is a mental one. Picture a map of the Puget Sound Region, with the Olympic Mountains on the left and the Cascades on the right. Now, superimpose a giant wagon wheel over it. At its most fundamental level, this is what the Puget Sound Region’s aquatic system looks like. Puget Sound is the hub, the Olympics/Cascades upland forests act as the rim and the river valleys serve the necessary function of linking the two. We know that we must clean up and soften the edges of Puget Sound, and wisely manage our forested uplands, but it is river valleys that are most stressed and at risk. Before European settlement, the Puget Sound lowlands were a spongy matrix of forests, streams and wetlands, providing critical habitat and producing a unique rain forest ecology. Today, after cutting, draining, paving and developing most of the Puget Lowlands, we expect our slender, damaged, delicate river corridors, along with some vestigial second growth forest patches, to shoulder the load of transporting clean cool water (along with natural sediment, nutrients and large wood) from the uplands and providing the riverine habitat on which many of our native species (and we) depend. This article highlights some of the conditions and activities we must continue to pursue if we are to maintain our regions’ ecological infrastructure. To accomplish this, I’ll take you on a visual trip upstream through one of my favorite watersheds. Well. . . They are all my favorites, but I happen to be most familiar with the Snohomish/Snoqualmie/Skykomish watershed. And, it’s largely happy picture, though we need to keep on with restoration and wise use efforts. A TRIP UP THE RIVER(S) Starting its mouth, the Snohomish River Estuary, the River has produced an enormous and dynamic delta fan with islands and off channels that remind This remarkable turn-around has been the result of many hands. Early on, many of the efforts came out of the 1997 Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan (SEWHIP) partnered by the City of Everett, Environmental Protection Agency, Puget Sound Water Quality Authority and the Washington State Department of Ecology. More recently, the Tulalip Tribes purchased 315 acres of former wetland, and after the regulatory and preparatory work, breached the restraining dike, established the Qwuloolt Estuary and opened the area to brackish waters that are now habitat to smelt and Coho Salmon, among other species.

And, while river channel movement is critical, so is farming. From an environmental perspective alone, farming is a preferred use (next to no use) in floodplains. In his Book, Saving Puget Sound, John Lombard names the future of agriculture as the “region’s most important land use issue” and notes: “If the choice is between development and farms, especially with farms with environmentally sensitive management practices, there is no question which is better for the region’s ecosystems”.  I’m not sure that the aerial perspective illustrates the sensitive management practices Lombard mentions, but it seems that it does, with ample setbacks

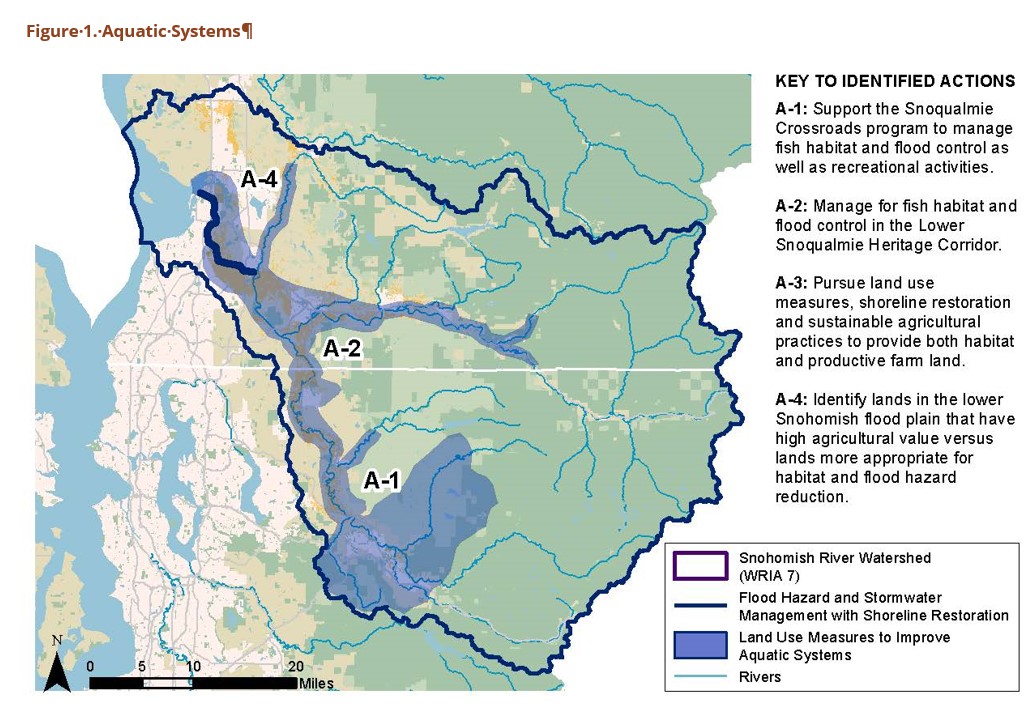

There are collaborative efforts in each of these segments to restore portions of the rivers and, at Because a river corridor’s ability to fulfill its ecological functions depends on its continuity – one break can disrupt the corridor both upstream and down – restoration and management efforts must be coordinated on a watershed basis. While individual segments can benefit from improvement efforts, the whole aquatic system must be considered. The Regional Open Space Strategy (ROSS) for Puget Sound exemplifies such an approach and provides a forum for coordinating such efforts for maximum benefit. The ROSS effort by the Bullitt Foundation Center, the University of Washington College of Built Environments (UW CBE), and the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), which included scores of participants included a case study illustrating a regional approach for the Snohomish watershed. The study identified numerous, potentially coordinated actions to be taken within the watershed and summarized priorities for aquatic system enhancements:

The map below from the Snohomish Watershed study illustrates these priorities. The study, being comprehensive in nature, also calls out priorities for biodiversity, agricultural lands, forest resources, community development, recreation and trails, and synthesizes the various elements into a comprehensive strategy.

THE NEED FOR A WATERSHED APPROACH TO ACHIEVE CLIMATE CHANGE RESILIENCY. As I suggested earlier, all of this is a relative happy story – but a happy ending is still in doubt. Two ominous trends threaten past environmental management successes: explosive population growth and climate change. Hopefully, enhanced growth management practices can mitigate the worst impacts of demographic growth, while realizing its benefits. This will require renewed effort for environmental protection as well as the growth of compact livable communities. Climate change is another matter. Although The ROSS was prepared early in the climate change debate, it identified three key threats to our river systems and to the region in general: flooding (of course), precipitation change (which threatens agricultural production and increases fire hazards), and rising temperatures (threatening human health along with fire danger) Flooding is the most obvious risk. FEMA flood hazard maps are no longer reliable. In December 2006 alone, the Snohomish County Emergency Management Department estimated $5.3 million in damage to farms along the Skykomish and Snohomish Rivers. Precipitation levels will also wreak havoc with farm production and fire management. Data from FEMA’s Representative Concentration Pathways analysis (RCP 4.5), as quoted in the ROSS, indicates that the average maximum temperature across the Snohomish watershed will rise by 2050 between 5.76 degrees F and 6.12 degrees F from 2000 conditions. The eastern portion of the watershed, with the forests and seasonal mountain snow, is expected to experience the most extreme effects.

Given the explosive growth of the Puget Sound Region and the effects of climate change, we must be prepared to invest effort and funds to sustain our river corridors as they will bear the brunt of climatic change and are critical resources within our urban-rural-wilderness fabric. And, as noted earlier, this can most effectively be done on a comprehensive watershed basis. Turn of the century scientists and planners analyzed the watersheds as part of the WRIA process to “save the salmon”. Now we must revisit this for implications to loss of human well-being. The ROSS has produced a useful tool to evaluate ecosystem services, including carbon capture and flood reduction, either by evaluating an individual land parcel’s contribution to a suite of services, or on a regional or watershed basis for an individual service (showing, for example, the most useful lands for carbon sequestration). Additionally, PSRC is currently working on a system to measure identified conservation needs. The tools are in place or emerging to coordinate climate change resiliency on watershed basis. So, we must take advantage of this opportunity. In the words of Steve Whitney, retired Senior Program Manager of the Bullitt Foundation: “A regional approach will be necessary if we are to achieve climate change resiliency”.

|

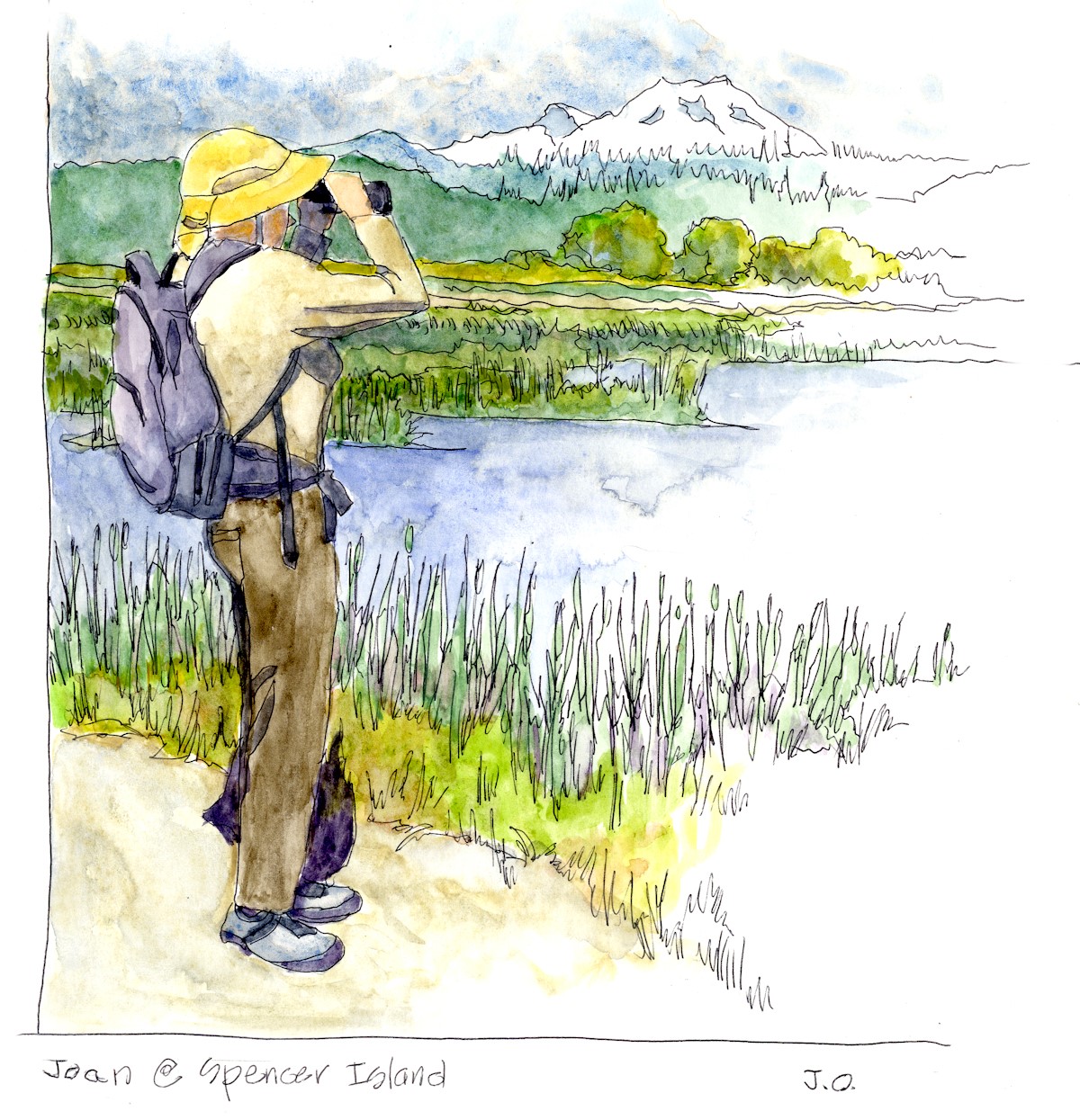

me of a Louisiana bayou without the cypress trees. When I started working on the river, about 35 years ago, these “bayous” were clogged with rafted logs being staged for transport to Everett’s pulp mills. If one visits today, they are presented with restored estuarine waters and wetlands. In fact, it is one of my wife Joan’s and my favorite bird watching spots.

me of a Louisiana bayou without the cypress trees. When I started working on the river, about 35 years ago, these “bayous” were clogged with rafted logs being staged for transport to Everett’s pulp mills. If one visits today, they are presented with restored estuarine waters and wetlands. In fact, it is one of my wife Joan’s and my favorite bird watching spots.  Travelling further upstream, one sees the typical morphological pattern of sinuous channels, oxbow lakes and patches of mixed vegetation characteristic of a low gradient river that is depositing sediment in some places and scouring it out in others. Below is one of my favorite views of the river (shamelessly cribbed from Google Earth) illustrating what I hope is an intimate integration of ecological functions and agricultural practices. This intimacy between farming and the natural river cycle is not implicitly friendly. A river’s “got to move” and farmers must protect their crops.

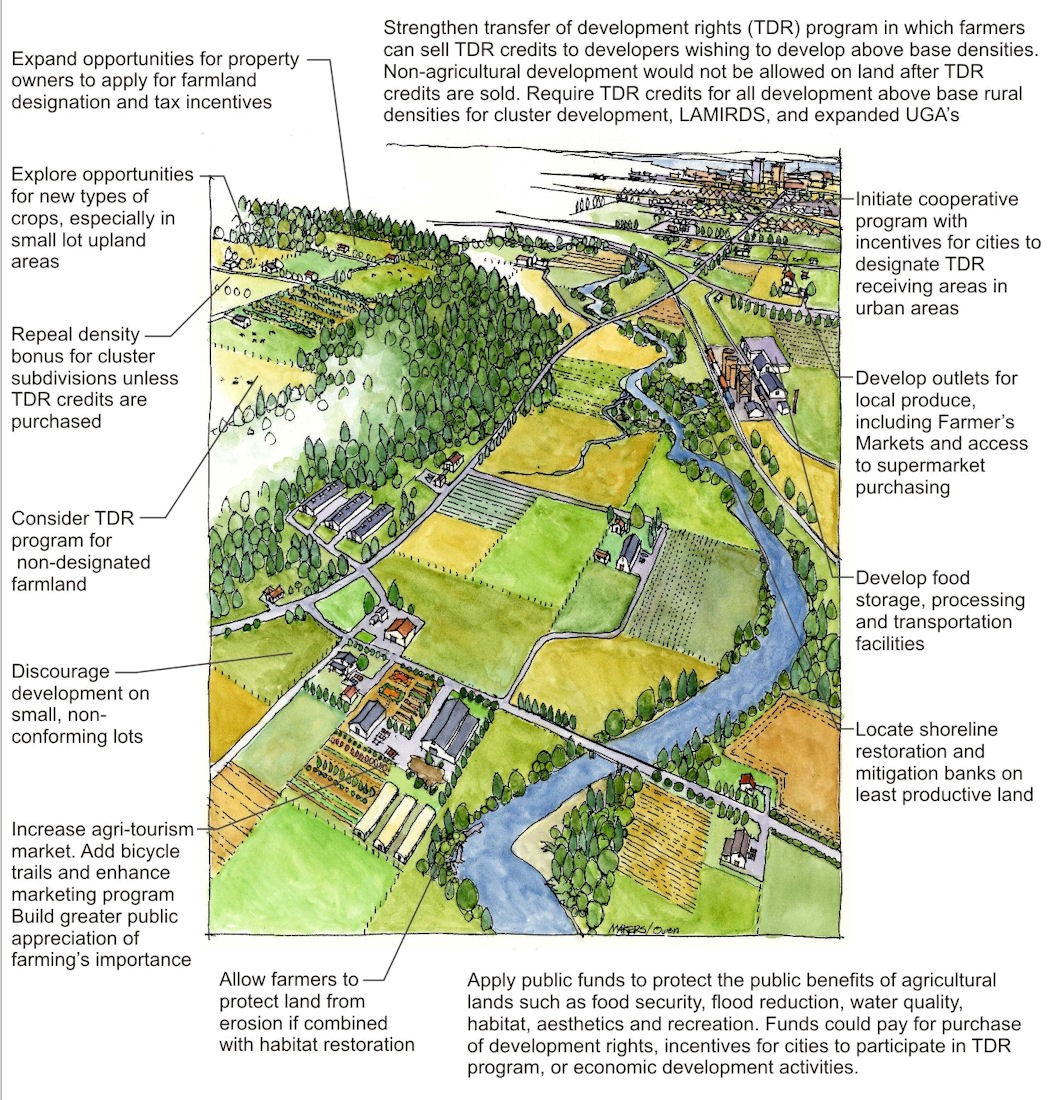

Travelling further upstream, one sees the typical morphological pattern of sinuous channels, oxbow lakes and patches of mixed vegetation characteristic of a low gradient river that is depositing sediment in some places and scouring it out in others. Below is one of my favorite views of the river (shamelessly cribbed from Google Earth) illustrating what I hope is an intimate integration of ecological functions and agricultural practices. This intimacy between farming and the natural river cycle is not implicitly friendly. A river’s “got to move” and farmers must protect their crops.  to row crops, lack of shoreline hardening and use of off-channel water resources. Some years ago, I used similar imagery in a poster to illustrate actions to integrate environmental and agricultural management practices. The project that it illustrated, Snohomish County’s Sustainable Agriculture program, now called the Agricultural Initiative, continues to be very successful in assisting local farmers and growers in their efforts. Additionally, Snohomish County’s Land Conservation Initiative is taking steps to preserve farmland and open space by purchasing development rights for agricultural land and open space.

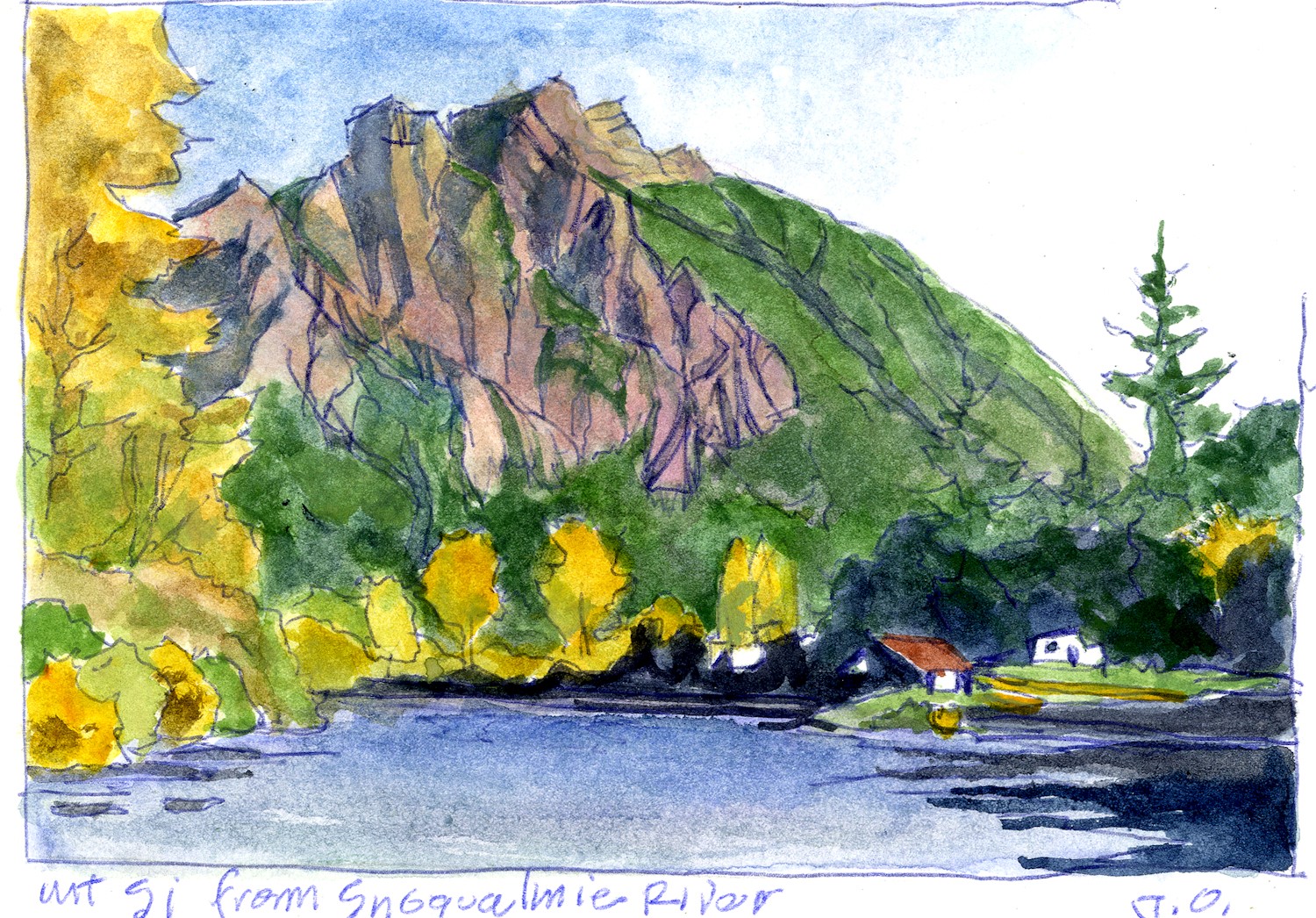

to row crops, lack of shoreline hardening and use of off-channel water resources. Some years ago, I used similar imagery in a poster to illustrate actions to integrate environmental and agricultural management practices. The project that it illustrated, Snohomish County’s Sustainable Agriculture program, now called the Agricultural Initiative, continues to be very successful in assisting local farmers and growers in their efforts. Additionally, Snohomish County’s Land Conservation Initiative is taking steps to preserve farmland and open space by purchasing development rights for agricultural land and open space.  Southeast of Monroe, the Snohomish splits into the eastward trending Skykomish and the southward bound Snoqualmie, both substantial rivers in their own right. Here again, there are several efforts to use the rivers’ assets while maintaining their ecological integrity. The “Sky” has potential as a recreational corridor while the Snoqualmie, like the Snohomish, features rich farmland that is becoming increasingly important. Further south and east, both rivers anchor a string of small towns along their banks, which are increasingly experiencing flooding challenges. Still further upstream, both rivers divide into their tributaries, many of which (but not all) are in managed or protected forest lands.

Southeast of Monroe, the Snohomish splits into the eastward trending Skykomish and the southward bound Snoqualmie, both substantial rivers in their own right. Here again, there are several efforts to use the rivers’ assets while maintaining their ecological integrity. The “Sky” has potential as a recreational corridor while the Snoqualmie, like the Snohomish, features rich farmland that is becoming increasingly important. Further south and east, both rivers anchor a string of small towns along their banks, which are increasingly experiencing flooding challenges. Still further upstream, both rivers divide into their tributaries, many of which (but not all) are in managed or protected forest lands.  the same time, encourage appropriate use. The Skykomish Scenic River Alliance has spawned a number of efforts to improve recreational opportunities along the river and ensure that the project improvements to US 2 will maintain the river’s scenic and ecological integrity. Construction has begun on King County’s 145-acre

the same time, encourage appropriate use. The Skykomish Scenic River Alliance has spawned a number of efforts to improve recreational opportunities along the river and ensure that the project improvements to US 2 will maintain the river’s scenic and ecological integrity. Construction has begun on King County’s 145-acre