- About Us

- Events & Training

- Professional Development

- Sponsorship

- Get Involved

- Resources

Sustainable WashingtonThe Climate Change Challenge“In the course of history, there comes a time when humanity is called to shift to a new level of consciousness, to reach a higher moral ground – a time when we have to shed our fear and give hope to each other. That time is now.”[1] Purpose of this DocumentIn 2002, the Washington Chapter of the American Planning Association published Livable Washington: APA’s Action Agenda for Growth Management. This landmark document was “offered as a touchstone to allow our members to join together to address the issues that affect our communities.” Livable Washington rightly celebrated our initial success during the first ten years under the Growth Management Act, while recognizing – through a wide-ranging set of policy recommendations – that further action was needed. Two years later, Livable Washington Update 2005 reframed these issues and offered an action plan featuring five major topics:

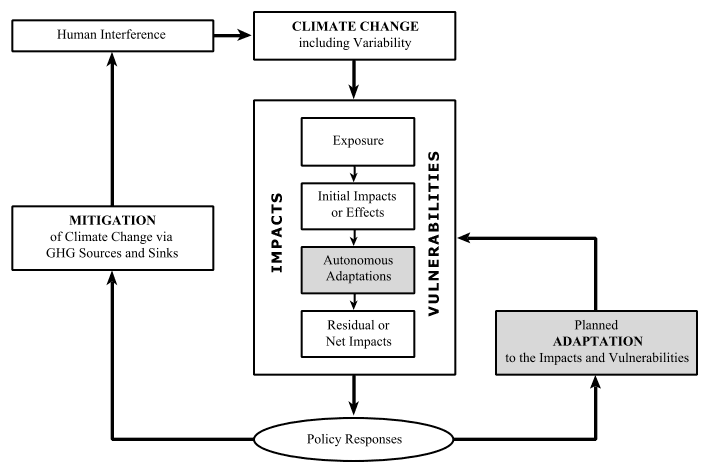

In 2015 the Washington Chapter of the American Planning Association created resources to address climate change as part of the Ten Big Ideas efforts. When the Growth Management Act was passed in 1990, global warming was a somewhat abstract concept well outside mainstream planning. Over the intervening twenty years, global warming has become better understood. Its consequences and impacts are not only real, but imminent. The growing consensus in the worldwide scientific community on the role of manmade (anthropogenic) greenhouse gases (GHG) in increasing global warming reached a critical milestone in February 2007 with the release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[2] (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report, (often referred to as AR4 or IPCC4). IPCC4 concluded that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal[3], and that “[m]ost of the global average warming over the past 50 years is very likely[4] due to anthropogenic increases.[5] Our understanding of global warming and the consequences for global climate change continues to grow rapidly. At a March 2009 meeting of the International Scientific Congress on Climate Change,[6] scientists agreed that the climate system is already moving beyond the patterns of natural variability, evidenced by changes in global mean surface temperature, sea-level rise, ocean and ice sheet dynamics, ocean acidification, and extreme climatic events. They report that scenarios considered “worst case” are already becoming reality and that, unless drastic action is taken soon, dangerous climate change is imminent (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of effects in Washington). Climate change is now emerging as the transformational challenge of the twenty-first century. This latest edition in the Livable Washington series is issued under a new name, Sustainable Washington 2009: Planning for Climate Change, reflecting both our increased understanding of livability in terms of sustainability and the critical issue of climate change. This edition is intended as a resource for Washington planners to use as we work to better understand the possible and likely environmental consequences of climate change, identify potential measures to help our communities adapt to the change, and reshape our built environment in ways that can mitigate the emissions of greenhouse gases. Key TermsThe following brief definitions of key terms are adapted from several sources to reflect how these terms are generally used in this report. Additional terms and more precise definitions of these terms, excerpted from IPCC’s Glossaries[7], are provided in the front matter of this document, following the Table of Contents.

Sustainability and the APAOver the last dozen years, as the evidence has mounted of the impacts of human activity on global carbon and hydrologic cycles, a new paradigm has taken hold – sustainability. Sustainability is much more than climate change – it represents a new, holistic way of looking at mankind’s relationship to natural systems, recognizing the interdependence of environmental, social and economic factors. The sustainability movement has grown throughout the domains of planning, environmentalism, and commerce, taking on additional flavors as the fundamental concept of living within the constraints of our ecological support systems is adapted to the range of human activity. What is sustainability? Over the past nine years, the National APA has focused on these issues with a series of Policy Guides. The Policy Guide on Planning for Sustainability (2000) recognized the importance of “a systematic, integrated approach that brings together environmental, economic, and social goals and actions directed toward the following four objectives:

A subsequent Policy Guide on Energy (2004) recognized the inherent problems of raising public awareness of energy issues and the limited, but central, role that planning occupies in dealing with this aspect of sustainability planning. The Policy Guide on Planning & Climate Change (2008) endorsed aggressive GHG reduction goals aimed at stabilizing global average temperatures at no more than 2°C (3.6° F) above pre-industrial levels. Our intent with Sustainable Washington 2009: Planning for Climate Change is not to repeat the work of these policy guides – although we encourage Washington planners to become familiar with these documents, as they provide valuable background for challenges at the local, regional, and state levels. Rather, our intent is to interpret the information from these and a wide range of other sources for the Washington situation and provide specific action items to serve as a resource for planners in our state. Preparing the DocumentThis document and its companion pieces (see Chapter 5) are the products of many people over many months of effort. (See the list of participants in Acknowledgements). The project was launched in earnest in January, 2009, as a follow-up to a brainstorming session in October 2008 at the APA Washington Chapter Conference in Spokane. Some 30 planners representing a variety of specialties, interest areas, and locations worked in teams of three to five people to prepare the specific action items presented in Chapter 3. The group met in a workshop format at the end of March to compare results, establish a common approach, and define the next steps. Throughout the spring, members of the group wrote, re-wrote, reviewed, and revised sections of the document. After study sessions with the Chapter Board and the Legislative Committee in June, the draft document was released for concurrent reviews by a group of selected experts and peers, as well as by all interested Chapter members. Following revisions based on those comments, the document was approved by the Executive Board in August 2009. We faced a number of challenges in preparing this document that shaped the final content and format:

Our decision to create a web-based document, rather than a printed product, is intended to make this massive amount information accessible and easy to navigate. As initially published, this document should be considered a starting point. We expect that the discussion and ideas contained here will expand with the science, and be further amplified as the range of responses and actions are explored. A Unique and Unprecedented ChallengeAs planners, our first duty is to the health, safety and well-being of our communities. Section A of the American Institute of Certified Planners (AICP) Code of Ethics clearly states that “Our primary obligation is to serve the public interest.” The Code also directs us to have “special concern for the long-range consequences of present actions” and to “pay special attention to the inter-relatedness of decisions.” The long range nature of climate change and the inter-relatedness of the causes and effects of climate change place this issue squarely within the purview and ethical responsibility of planners. Fulfilling this responsibility requires that we educate both ourselves and our communities to ensure that Washington communities are prepared to deal with the impacts associated with climate change. As we are writing this document in 2009, it appears that many communities are not prepared. The National Academy of Sciences publication, Informing Decisions in a Changing Climate[11], noted this stark reality: Why governments cannot wait

Our purpose in presenting Sustainable Washington 2009: Planning for Climate Change is to help planners in Washington prepare to address climate change issues and to provide specific action items that planners can take to make a difference. Washington APA Principles for Climate Change ActionIn preparing this document, the planners involved developed a set of guiding principles that serve as the foundation for recommended actions. With the action to approve publication of this document, the Washington Chapter APA has approved and endorsed these principles.

Washington as a LeaderWashington’s cities and counties have been among the leaders in U.S. local governments in planning for climate change. In 2005, Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels challenged the U.S. Conference of Mayors to meet or beat the Kyoto Protocols established for international agreement on reducing global warming pollution levels. His original target, to gain agreement among 144 cities, was intended to match the number of countries which had signed the Kyoto Protocol. By 2009, a total of 956 U.S. cities, representing over 83 million citizens in all fifty states (and over 25% of the U.S. population) have signed the U.S. Conference of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement. In 2005, King County’s Climate Change Conference brought together more than 600 government, business, and community leaders to open a dialogue about climate change impacts and potential adaptations. This conversation has continued through the joint efforts with ICLEI - Local Governments for Sustainability and the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group resulting in the publication of Preparing for Climate Change: A Guidebook for Local, Regional, and State Governments. Planning for climate change has not been limited to larger cities and counties. Olympia’s Climate Action Plan, developed in 1991, was one of the first in the U.S., and served as the beginning of a long commitment to mitigation and adaptation. Smaller towns throughout the state – including Port Townsend (population 8,300), Washougal (population 14,000), and Langley (population 1,000) - are also taking aggressive actions to address climate change challenges. Guide to this DocumentThis document is organized into five chapters. In Chapter 2, we provide an overview of the scientific studies on climate change, describe the scientific projections for impacts in Washington, and examine greenhouse gas emissions in our state.

In Chapter 4, we look at Washington’s responses to sustainability and climate change from a legislative standpoint, discussing past and current legislation. Also, we look at Washington’s Growth Management Act (GMA) and how planning under GMA can be a means of addressing climate change. In Chapter 5, we return to the issue of planners’ roles and discuss how planners can integrate their efforts with those of other professions and other disciplines. This section also explains the information suite that APA Washington has prepared to help planners respond to this challenge. Appendix materials include:

Footnotes 1 Wangari Muta Maathai, Kenyan environmentalist and founder of the Green Belt Movement. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2004/maathai-lecture-text.html |