- About Us

- Events & Training

- Professional Development

- Sponsorship

- Get Involved

- Resources

Sustainable Washington3.9 Social EquityThe planning profession has a responsibility to promote social equity and environmental justice for Washington state residents through the plans, policies, and programs that we develop, especially in planning for the mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change. Each of the topics included in this document has an inherent social equity component. This section takes the discussion one step further by identifying additional social equity issues and offering some public policy strategies. What is Social Equity? The National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) defines social equity as: “When the floodwaters rise, fires wage, droughts parch, or super-diseases attack, the most marginal cannot afford to get out of harm’s way. They cannot afford to protect themselves. And still worse, once the crisis has passed, they are least able to bounce back, to rebuild, to recover.” Environmental justice is the equal protection of minority and low-income populations from environmental hazards. Often this designation is broadened to include especially vulnerable populations such as the disabled, the elderly, the very young, and populations with limited English proficiency. The goals for environmental justice and social equity promote public policy that includes fair and equitable procedures, regulations, and outcomes. A number of cities are preparing plans to address sustainability and climate change issues, including a focus on social equity. See the description of the plan prepared by the City of Vancouver, Washington, as an example. It is becoming more evident that those who have contributed the least to factors that cause climate change are those who are potentially most vulnerable to the negative consequences of climate change. Hurricane Katrina made this tragically clear when vulnerable populations were those most greatly affected not only by its widespread devastation but also by the unequal provision of services and resources following the event. In 1994, Presidential Executive Order 12898 mandated: “Each Federal agency shall make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations.”[3] Identification of Location and Needs of Vulnerable PopulationsChildren, the elderly, immigrants, minorities, lower socioeconomic families and adults, and the disabled are often underrepresented within the decision-making bodies and processes for establishing social policy. A resultant consequence is that these vulnerable populations are frequently underserved by infrastructure and services. A key component to serving these vulnerable populations is to know their numbers and locations within urban and rural communities. Thus, mapping population by demographic data is the first step to identification of vulnerable groups and their needs.

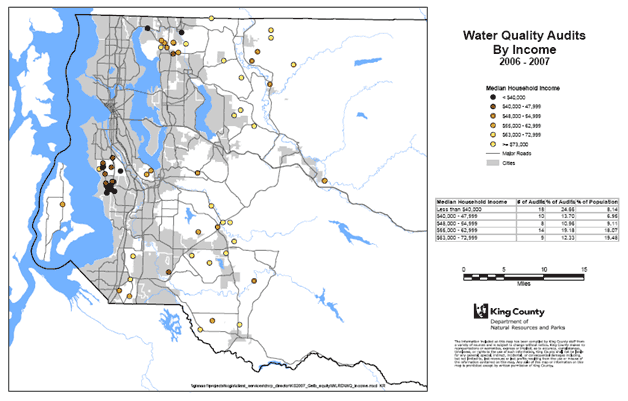

Secondly, identification of need should be undertaken to ensure that resources can be efficiently and effectively allocated amongst population groups with similar needs. For example, the elderly and lower income adults have a greater than average need for transit. Often the provision of services can be beneficial to multiple groups. For example, curb cuts benefit the elderly and those who are mobility-challenged, including young families with children in strollers. Social impact assessment can be a useful tool to help evaluate policy alternatives and to formulate effective, equitable public policy. King County’s Department of Natural Resources and parks is conducting an equity assessment of its services, see Project Example #2. Arrival of a New Vulnerable PopulationThere has always been an influx of immigrants to the United States for a variety of social, economic, and political reasons. However, climate change may add a significantly large population of climate refugees who have been dislocated from their homes due to rising sea levels and other environmental hazards resulting from climate change. In 2005 there were estimated to be 25 million climate refugees world-wide, with this number potentially rising as high as 50 million by 2010, according to Professor Norman Myers of Green College, Oxford University[4], and possibly as high as 150-200 million refugees by the year 2050. Rising sea levels will account for some of these climate refugees, which will likely include populations within the U.S. such as residents of the Gulf Coast. The challenge will be to accommodate this population influx and meet the needs of existing residents. In addition to broader issues of social equity, this section focuses on four issues of particular importance for vulnerable populations:

ActionsThe following list of actions is separated into three categories: Getting Started, Making a Commitment, and Expanding the Commitment. This graduated approach allows jurisdictions to implement measures that are appropriate to their community’s current level of involvement in climate change and sustainability issues and in consideration of locally adopted plans, codes, regulations, policies and goals. SE-1 Mobility and AccessibilityPromote mobility between housing, employment, and essential services, especially for vulnerable populations. Encouraging proximity of uses can reduce the need for auto-dependent travel. Getting started3.9.1 Identify and map transit, bicycle, and pedestrian infrastructure.Map the location of existing and planned transit facilities and services relative to the location of areas of low income and affordable housing, public services, and employment centers. (Local and Regional Action) Example: Seattle Bicycle Master Plan. Seattle Department of Transportation. 2007. Identify potential rights-of-way and easements for multi-use trails to promote transportation for recreation and commuting for vulnerable populations. Identify any gaps along significant travel corridors. (Local and Regional Action) Example: Hennepin County Bicycle System Gap Study. Hennepin County, Minnesota. 2001. Making a Commitment3.9.2 Involve underserved residents in planning for transportation infrastructure.Choose culturally relevant methods for public participation and solicit information regarding any barriers that limit mobility and choices, such as safety issues and transit service routes and schedule. (Local and Regional Action) 3.9.3 Address areas of inequity in delivery of key services.Through outreach, public participation and community indicators, identify areas of inequality in availability or use of transportation and delivery of services. Identify potential partnerships and resources to expand services. (Local and Regional Action) Tacoma’s Community Based Services Program illustrates one way that cities are customizing services for neighborhoods of higher need. See Project Example #3.

Example: King County, WA evaluated the proximity to and use of parks and trails by minority and lower income populations. Gelb , Richard. King County, WA: Performance Management Lead at King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks. Using Community Indicators and Performance Measures in Advancing Toward Sustainable Outcomes. September 12, 2008 Power Point. Expanding the Commitment3.9.4 Promote innovative transportation for different population groups.Provide incentives for reducing the need for personal automobile ownership. Promote car sharing for residents of multi-family housing and retirement communities and ensure that all populations have access to these programs. Explore the use of electric vehicles within retirement communities. (Local, Regional, and State Action) Example: A car sharing program in Chicago serves thirty-two neighborhoods and planned developments. Cohen, Adam; Shaheen, Susan; McKenzie, Ryan. Carsharing: A Guide for Local Planners. American Planning Association-PAS Memo. May-June 2008. Example: Golf carts utilized in Palm Desert, CA. for pilot transportation program. Golf Carts making the Rounds in Some Communities. University of Southern Florida. 1998. 3.9.5 Encourage affordable housing near transit.Provide height bonuses, reduction in minimum lot sizes, and other incentives to encourage affordable housing within walkable distances to public transit. (Local and State Action) 3.9.6 Establish policies for innovative mixed uses.Incorporate innovative mixed- land use policies in comprehensive plans and zoning regulations in order to provide affordable housing in proximity to retail uses and professional and personal services. (Local and State Action) Example: Vivian McLean Place, Seattle, WA with 19 affordable apartments above a library in Delridge neighborhood. Delridge Neighborhood Development Association. Example: West Seattle Food Bank and Resource Center offers 34 affordable apartments located above a food bank. Three projects; One Community. SE -2 Environmental HazardsLessen the impact of environmental hazards (such as heat waves, drought, flooding, and forest fires) particularly on vulnerable populations. Getting started3.9.7 Identify and plan for use of community buildings for temporary shelter.Effectively disseminate information to the public about shelters from storms or cooling centers. (Local and Regional Action) Making a Commitment3.9.8 Develop programs and regulations to minimize and reduce the risk of hazards, especially to vulnerable populations.Develop programs directed to residents to reduce the incidence and possible impact from hazards, such as flooding, fires, and sea level rise. For example, fire risk could be lessened by providing funding programs to help homeowners to replace roofs with fire-resistant roofing materials. (Local, Regional, and State Action) Expanding the Commitment3.9.9 Develop incentives for construction of affordable, naturally cooled homes.For portions of the state that experience high temperatures, develop incentives for construction of affordable housing designed for natural cooling to minimize the need for air conditioning and resultant energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. (Local Action) Example: Utilize innovative design and technologies to reduce heat gain within buildings and to promote cooling, including: convective, evaporative, and radiative cooling. See Arizona Solar Center. 3.9.10 Regulate development in areas identified as high risk for flooding or forest fires.Assist vulnerable populations in reducing risks from environmental hazards through design (e.g., elevated homes in flood areas, fire retardant materials in fire areas). Utilize federal and state funding sources and TDR programs to acquire property or development rights in high risk areas to retain these areas as undeveloped buffers. (Local and State Action) SE-3 Affordable, Adaptable, Energy-Efficient HousingProvide affordable, adaptable, energy-efficient housing that meets the needs of all populations. This will achieve multiple benefits, including reduction in energy use and unnecessary demolition, thus reducing greenhouse gas emissions for energy and materials production. Getting started3.9.11 Implement a home weatherization program for low income residentsMake use of state and federal funding programs for home weatherization targeted to low- and medium-income households. (Local and State Action) Example: City of Seattle HomeWise program. City of Seattle. About HomeWise Home Improvement Services: Repairing and Weatherizing. Making a Commitment3.9.12 Encourage rehabilitation of housing and infill development.Maintain adequate housing stock for available lower income and immigrant groups. Promote regulations that allow accessory dwelling units within areas zoned for single-family residential in order to accommodate multi- generational families. Increased housing and population density can provide the economic base to support commercial and other services within a walkable distance, thus, decreasing the need for vehicle trips. (Local Action) Example: City of Mercer Island regulations for accessory dwelling units. Accessory Dwelling Units City of Mercer Island, WA. 19.02.030. July 2008. Expanding the Commitment3.9.13 .Adopt building regulations and policies for new and existing residential structures that meet the principles and features of “universal design”. These design standards increase the adaptability and appeal of structures to people of all ages and abilities, including the increasing elderly population. (Local and State Action) “Universal Design and green design are comfortably two sides of the same coin but at different evolutionary stages. Green design focuses on environmental sustainability, Universal Design on social sustainability.”[5] Embracing both sustainable features and universal design encourages a more adaptable, energy-efficient building, thus, resulting in a longer lifespan and smaller carbon footprint. Example: Renovation of an existing home in Washington D.C. for six independently living seniors. Tour Northeast D.C. Home Transformed with State-of-the-Art Universal Design. 3.9.14 Adapt existing buildings for low income housing.Adopt regulations and provide incentives for retrofitting of existing structures for energy efficiency and adaptive reuse. Provide low- and medium-income housing. See the Land Use section for further information. (Local Action). Example: Build housing at declining malls. 101 Uses for a Deserted Mall. New York Times. April 4, 2009. SE- 4 Climate RefugeesProvide for the needs of the projected population influx due to climate change. These needs will include housing, employment, and schools. Planners can encourage these challenges to be met in a coordinated, organized manner within their individual jurisdictions. The following are some of the challenges that Washington State will be presented by the arrival of climate refugees:

Getting started3.9.15 Plan for climate refugees.Encourage local officials and agencies to plan for the temporary and permanent housing, employment, and social services needed by climate refugees through a coordinated plan at state and local levels. Encourage opportunities for public input to this plan. (Local and State Action) Footnotes 1 National Academy of Public Administration, Standing Panel on Social Equity, Issue Paper and Work Plan. October 2000; amended November 16, 2000. 2 Jones, Van. The Green Collar Economy; How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems. New York: HarperCollins. 2008. Pg. 66. 3 Environmental Justice, U.S. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration,. 4 Myers, Norman. Visiting Fellow, Green College, Oxford University. Environmental Exodus; An Emergent Crisis in the Global Arena Climate Institute. 1995. 5 Institute for Human Centered Design; Adaptive Environments. Additional Sources

|