- About Us

- Events & Training

- Professional Development

- Sponsorship

- Get Involved

- Resources

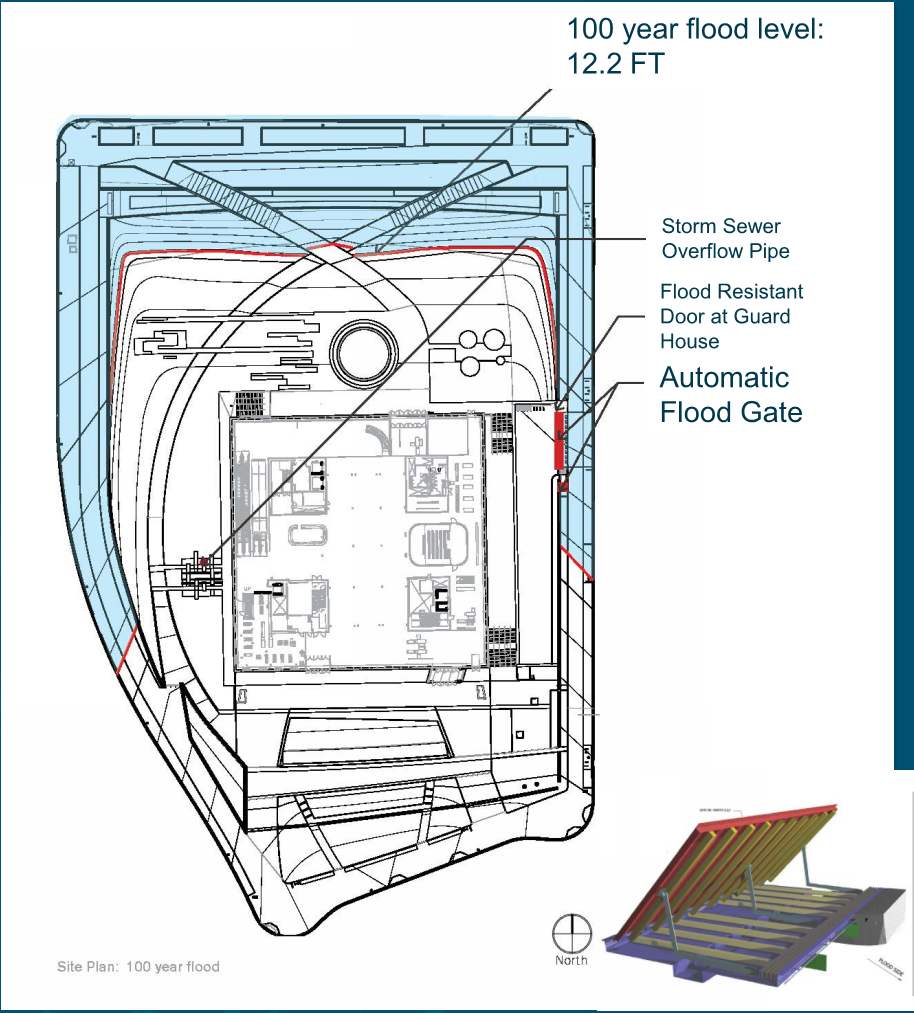

Climate Adaptation in and Around the Other WashingtonThe Ten Big Ideas Initiative is an APA Washington Chapter program designed to bring about far-reaching and fundamental change on a variety of issues. In this series, The Washington Planner will focus on communities taking action to respond to climate change, providing Washington APA members with more information on the work being done, and how they can take action in their community. We take a break from featuring a local community in Washington State to look at climate adaptation efforts in the National Capital Region (NCR), where governance is a major challenge for 21 jurisdictions from 3 states: Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia. Despite this major challenge, the NCR has demonstrated leadership in advancing climate change policy, through three executive orders and a diverse array of state and local policies. This paper will focus on flooding as a climate risk that has prompted regional coordination, and feature on-the-ground adaptation projects that resulted from the regional efforts. The National Museum of African-American History and Culture (NMAAHC) opened two months ago with much fanfare. Media coverage included the beautiful design of the building, the fundraising efforts, and the treasures within its walls. It was, to many, a historic moment; an acknowledgement of the struggles and resiliency of African-Americans in the U.S. But what many did not know is that it captures another historic kind of resiliency – climate change. The museum is the first building in the National Mall designed with the future climate change realities in mind. The site is at the lowest point of a large urban watershed that includes the U.S. Capitol and the White House, and vulnerable to flooding. In the last 8 years, the regional stakeholders, including the federal government, the Government of the District of Columbia and the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCOG) have collaborated in climate resiliency efforts, after a wake-up call in June 2006. After 5 days of continuous rain, a major flash flood on Constitution Avenue between the White House and the U.S. Capitol (a.k.a. the Monumental Core) flooded the basements of the National Archives, two Smithsonian museums, the federal headquarters of the Department of Justice, the Internal Revenue Service, Department of Commerce, and the Environmental Protection Agency (how ironic!). The regional infrastructure systems, including Metrorail, the power supply, and the roads were shut down for several days. This rain event was comparable to a 200-year storm event. In response, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) convened 14 local governmental departments, regional infrastructure agencies, and federal stakeholders to evaluate alternative solutions to prevent the future flooding of the Monumental Core. While most flood mitigation plans looked to historical conditions for baseline data, the working group looked at a future scenario of more extreme and frequent storms to simulate a warmer climate of the future. It also looked at the use of LIDs as one of the flood prevention alternatives.  Figure 1. Site Plan of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture featuring area vulnerable to flooding (blue) and berm with automatic flood gate to protect the building. (image courtesy: Smithsonian Institution) This was the first time the future risk of climate change was factored in a technical study for a real geographical area in the National Capital Region. The study provided the technical guidance for the Smithsonian Institution, the General Services Administration (GSA), the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (which includes Metrorail), and the National Archives to upgrade the flood protection measures for their facilities. The study also informed the design of the new NMAAHC.  Figure 2. National Museum of African-American History and Culture self-rising floodgate under construction (image courtesy: Smithsonian Institution) Following this successful collaboration, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and FEMA sponsored a floodproofing seminar. While the sponsors provided technical resources to the participants in the first half of the day, the afternoon showcased the innovative flood protection measures implemented by the agencies whose facilities flooded in 2006. GSA raised the central mechanical and electrical equipment of the Department of Commerce above the first floor of the new wing. The National Archives provided an on-site demonstration of its new self-rising floodgates. The National Gallery of Art shared “lessons learned” in their use of Aquadams. The Smithsonian showed the plans for an integrated flood protection and security berm for the NMAAHC. The NMAAHC is designed to withstand a 500-year flood of the Potomac River for the subterranean levels of the museum and a 200-year 6-hour storm for an interior drainage flood for the surface above (the cause of the 2006 flood was not riverine flooding, but interior drainage). In a region where interagency cooperation even among the federal government agencies is difficult, the working group became an ad hoc partnership where anyone interested in climate adaptation efforts in the NCR could join. The very same week that Superstorm Sandy hit the East Coast, NASA, GSA, the U.S. Global Change Research Program, the National Capital Planning Commission, and the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments partnered together for an initiative to offer a series of webinars and workshops in climate adaptation risk assessment for the region’s stakeholders. By this time, the Obama Administration has further expanded the mandate of Executive Order 13514, to direct federal agencies not only to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, but to also assess the vulnerability and risks of climate change in their respective missions. The clear mandate from the White House helped to obtain the support of the senior executives of federal agencies to participate in the training. The partners used the workshop to increase awareness among the various agencies at all levels of government on their interdependencies, and to facilitate the dialogue on the challenges of working on a common set of adaptation priorities. Climate risks identified include those due to long-term, incremental changes, as well as extreme weather events. Sectors analyzed included water, public health, infrastructure and buildings, energy, and the natural environment. To ensure that the momentum continued, the National Capital Planning Commission facilitated monthly meetings for the regional stakeholders where new climate adaptation initiatives from the member agencies are featured. Among them were the District of Columbia Climate Change Adaptation Plan, the new seawall for the Blue Plains Wastewater Treatment Plant, Vulnerability Assessments by the National Park Service, and a series of policy discussions on infrastructure resiliency. The Blue Plains seawall project is notable for building the seawall with a 3-foot freeboard to account for sea level rise and storm surge due to extreme storms. Despite the lack of support from Congress, the federal agencies and the local governments in the National Capital Region were able to take steps to start adapting to climate change. Without direct funding for climate change policy implementation, the interagency working group leveraged each other’s technical expertise and funded projects to advance best practices in climate adaptation. Background reports for climate adaptation initiatives mentioned here can be found in the Metropolitan Washington Council of Government’s website: https://www.mwcog.org/environment/planning-areas/climate-and-energy/climate-preparedness/ General resource for local communities, with case studies including projects can be found on the EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/arc-x/searchable-case-studies-climate-change-adaptation Stepping up to address Climate Change at the state, regional, and local levels is one of the Ten Big Idea Initiatives. This work culminated in a short video focusing on the science of climate change, highlighting actions of three local communities, and a Resilient Washington document - 17 written discussion briefs addressing adaptation and mitigation strategies for local governments. The briefs are grouped in three sections - Planning Approaches for Resilience, Strategies for Planning Resilient Communities, and Preparing for Climate-Related Events. The video and discussion briefs can be found at http://www.washington-apa.org/address-climate-change. Return to the November/December issue of The Washington Planner |